Malabar

Botanical Gardens > Malabar

Drawing Hortus Malabaricus

In 1678, a pioneering and extraordinary Dutch botanical text – with extraordinary botanical art – began to take shape on India’s Malabar coast: Hortus Indicus Malabaricus, Continents Regni Malabarici apud Indos celeberrimi omnis generis Plantas rariores, 1678-1681. Or Hortus Malabaricus for short. Latin for the Garden of Malabar. [1]

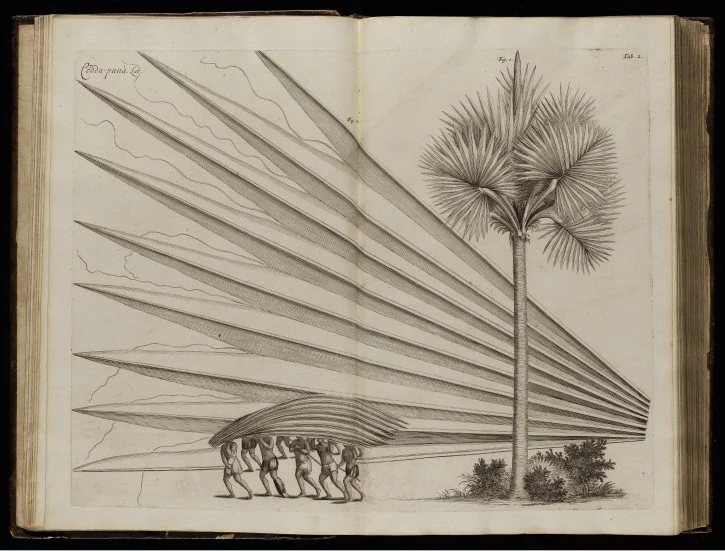

Hortus Malabricus was commissioned by the Dutch East India Company’s governor of Cochin, Hendrik Van Rheede. Begun in 1673, this 12-volume masterpiece took more than a decade to complete and marked a climax in late 17th century botanical literature as the first definitive history and survey of tropical botany in South Asia. The exquisitely illustrated volumes included wide-ranging information on the medicinal uses of 740 plants, most accompanied by double folio copperplate engravings, which were valuable not only because of detailed depictions of the flora of Malabar that drove commercial trade routes and colonial exploration, but also because of their seminal influence on the scientific development of botany, tropical medicine, and medicinal gardens in cosmopolitan centers of learning like Leiden and Padua. Van Rheede’s conceptualization of Malabar as “the garden of the world” persuaded him to make a more fundamental set of associations between landscape and people, and between forests, medicine, and health, all of which were to have a decisive impact on Dutch colonial responses to deforestation.

Hortus Malabaricus' impact on botanical science was, without a doubt, global. We know now that it was the main source for Carl Linnaeus's knowledge of Asian tropical flora, which in turn critically influenced the development of species taxonomy in his 1753 opus, Species Plantarum - and from there, to the binomial classification in use today. Even more interesting in the world of 17th century colonial botany, Hortus Malabaricus had unusual epistemological significance in its reliance on local medical knowledge. Unlike other illustrated herbals compiled at the time, Van Rheede relied almost entirely on indigenous collaborators: three Konkani Brahmin scholars – Ranga Bhatt, Apu Bhatt and Vinayak Pandito (Apu Botto, Ranga Botto, and Vinaique Pandito) - who provided textual and scholarly reference, but more importantly, Ayurvedic physicians from the Ezhava or low-caste toddy tappers, who provided the empirical plant knowledge and functional taxonomies of classification.

ARTISTS, ENGRAVERS and COLLABORATORS

Itty Achuden

Apu Bhatt, Ranga Bhatt & Vinayaka Pandit

Antoni Goetkint

Marcelis Splintjer (artists)

Bastiaan Stoopendael

Gonsalez Appelman

(engravers)

Father Matthew (artist)

in Viridarium Orientale

Istoria Botanica

Rariorum Stirpium Historia

The main Ezhava informant was the well-known healer, Itty Achudan, who selected, procured, and classified the plants for inclusion in Hortus Malabaricus. Achudan was considered so influential that an entire plant genus was named after him, Achudemia. In privileging the Ezhava, or non-Brahmin view of the world, Van Rheede transformed not only Ayurveda (often understood as an orthodox elite tradition) but also, according to some scholars, colonial botany and thus Western science itself. Ezhava botanical classifications and medicinal garden schemes – organized and named according to functional taxonomy, i.e. how they were used rather than their structural morphology -- were recreated intact in Leiden’s famous botanical garden, Hortus Botanicus. But the real irony here is that although Ezhava ethnobotanical information may live on in global science, the actual role of Ezhava informants has long been forgotten. Local Ayurvedic knowledge may have transformed the origins of medical botany and Western science but has been written out of history.

The text’s drawings, however, tell a different story of archival forgetting and art production. Above and beyond its role as repository of medico-botanical and indigenous knowledge, Hortus Malabaricus is an uncommonly beautiful art object in itself – with uncommonly beautiful botanical art between its covers. As mentioned earlier, Company-era botanical art forms a small sub-genre of what has been known as Company School (kampani kalam) art, a broad term for a hybrid genre of Indo-European paintings that developed in India in the 18th and 19th centuries by native Indian artists under the patronage of the British East India Company. Historically, Company School botanical art was thought to reflect a unique visual conversation between the non-botanist Indian artists and the Company botanists and administrators; a tension between the naturalistic depiction of individual ‘specimens’ drawn from empirical observation advocated by Western science, and the stylized, flat, intimate depiction of composite ‘types’ common to narrative traditions in Indian genre or miniature paintings.

And indeed, this is the case with some of the British Company botanical paintings of the 18th and 19th centuries, especially those in North India, made by artists who had been trained in miniature traditions of the late Mughal period. But what are we to make of pioneering Dutch East India Company botanical art in texts like Hortus Malabaricus, which defy common understandings of Kampani kalam on so many levels – in terms of the artists (Dutch military artists, not Indian), the period (late 17th century), the region (Dutch Malabar), the style (detailed copperplate engraving with more fanciful original drawings that show influence of European baroque), and even in terms of art process and production (drawn in Cochin, its 12 volumes printed in Amsterdam over 30 years).

I would suggest that it is this art history of Hortus Malabaricus – what we know about the making of 17th century Dutch East India Company botanical art in printed form – that tells its own story of globalization. Of how original drawings of plants in situ, gathered from the colony (Malabar) interacted with print technology of copperplate engraving in Dutch colonial metropoles (Leiden, Amsterdam). And of the artistic process by which botanical art was created on the page by Dutch military artists in dialogue with local scholars and Dutch VOC officials, but also in conversation with Baroque styles of book illustration (which featured text cartouches and imaginary or fabled beasts and animals), and late 17th century Dutch and Flemish painting styles dominated by still-lifes, mannered interiors, and perspective realism. Of how Dutch Company art, exported from the Malabar it was meant to represent created and inspired Science, just as Company Science would come to rely on Art for its visual representations of tropical botany.

What did the art of Hortus Malabaricus look like and who were these artists? The 742 copperplate engravings themselves were based on monochrome ink wash drawings, the original (and only surviving) copies of which are now preserved in the British Library’s manuscript room. Collectively known as Horti Malabarici Icones, these codices of unpublished drawings correspond to engravings made for the first ten volumes of Hortus Malabaricus (the very last codex, containing drawings corresponding to volumes 11 and 12, has been missing from the time of acquisition in 1771).

We have the names of only two artists of these original drawings – Antoni Jakobsz Goetkint and Marcelis Splintjer – even though reference is made to a few others who remain unnamed. And indeed, only two among the 742 drawings bear artist signatures. Here is one of them signed by Antoni Goetkint: a drawing of Malabar’s ubiquitous coconut tree that provides the basis for what became one of Hortus Malabaricus’ most celebrated engravings in print. Goetkint’s signature is in the lower left corner of the drawing (on the left) as well as in the engraving made from this drawing for Hortus Malabaricus. In the engraving (on the right), the artist’s signature is included along with the name of the engraver, xxxx.

Original ink-wash drawing of Tenga by Antoni Goetkint, Horti Mabaricii Icones, mss 1. Source: British Library

Copperplate engraving of Tenga by Bastiaan Stoopendael (after drawing by Antonin Goetkint, left), Hortus Malabaricus, Volume 1, 1678. Source: Wellcome Library

Nor was the print production of the first Latin edition of Hortus Malabaricus any less complex than the commission of drawings – and in fact, the print process reveals much about Company gardens – at least some of which might have comprised what is today known as ‘Odatha’ (which literally means 'garden' in Malayalam) in Fort Kochi – and VOC political centers Cochin and Batavia as points of art production. While the drawings of tropical Malabar plants were done in Cochin (in situ and through field observation), the watermarks of paper used tell us that they were taken to Batavia by Van Rheede, and later made into copperplate engravings in Amsterdam and Leiden, far away from the tropical gardens that they represent and that give them context. Indeed, all twelve volumes of Hortus Malabaricus were printed in the Dutch metropoles (clearly shown by watermarks and printing technologies), and Hortus Malabaricus was only the third book to be printed with Malayalam names.

But just as the artists were invisible and anonymous, so too were the engravers. Of the 742 uncoloured engravings in all (721 in double folio and 79 in folio), every one of them was carefully copied from the original drawings though in reverse and with additions and omissions of leaves, flowers, fruits and seeds, as well as omissions of the the more fanciful cartouches and insets that featured dragons and mermen and other allegorical figures from the European baroque. However, as with the drawings, only two engravings in the entire 12 volumes have been signed by the engravers – Tenga /Coconut (volume 1) by Bastiaan Stoopendael and Hina paretti (volume 6) by Gonsalez Appelman.[1] Heniger goes on to say that the great stylistic uniformity of the engravings does not allow a detailed analysis of individual contributions, although the plates differ slightly in execution of Roman characters. The beautiful copperplate engravings of the Hortus Malabaricus – the garden of Malabar – were in fact printed in Amsterdam, far from its Dutch colony on the west coast of India whose plants it represented. In this respect alone, this particular picture book with its East-West twain (that never met) might be seen as Kiplingesque

Most accounts tell us that the Hortus Malabaricus engravings were the first pictures of Malabar flora to have reached the West. But were they really the first? And this is where further research reveals a fascinating addendum to this botanical art story. Following leads suggested by J. Heiniger, research reveals an alternative set of botanical drawings of Malabar flora by a Carmelite priest, Father Matthew, which in their introductions to the West may have preceded Hortus Malabaricus by an entire decade! Father Matthew was on the Hortus Malabaricus’ original team of collaborators, and it is possible that Van Rheede initial conception of the volumes may have been inspired by Fr. Matthew’s extensive knowledge and drawings of the Malabar flora, and his travels along the coast of present-day Kerala. Even though Van Rheede was to later reject Fr. Matthew’s drawings for the Hortus Malabaricus (claiming they were not life-like nor identifiable nor drawn in situ), he was to generously credit Father Matthew as the original ‘conditor’ or founder of Hortus Malabaricus.[2]

Even more interesting is the fact that Father Matthew’s drawings may have been the first representations of Malabar flora to make their way into print in the major Italian botanicals of the time (Viridirum Orientale, Zanoni’s Istoria Botanica, and Monti’s Rariorum Stirpium Historia). Indeed, Matthew’s Viridium Orientale – which is comprised almost entirely of his sketches and notes before 1674 -- can be seen as a model of the first draft of Hortus Malabaricus (Heniger, 1986). A proto-Hortus Malabaricus that led with the Art. Father Matthew’s drawings (in the Paris codex of the Viridarium Orientale) and engravings in Italian botanicals of the late 17th century may have been the real and original pioneers in Malabar botanical art. The original introduction of Malabar flora to the West.